Prime Minister Ishiba responded swiftly to the November 5th US presidential election.

When Trump declared victory on November 6th (Japan time), Ishiba immediately sent a congratulatory letter in which he “expressed that he would like to work closely together to further strengthen the Japan-U.S. Alliance, which is a top priority of his administration, and to realize a Free and Open Indo-Pacific“.

On the morning of November 7th, they held a roughly five-minute phone conversation, confirming their intention to deepen the Japan-US alliance further. Ishiba remarked that the call felt “very friendly.”

According to reports, he is considering stopping in the United States on his way back from the G20 Rio de Janeiro summit on November 18-19 to meet Trump in person.

The sequence of events closely mirrors 2016, when former Prime Minister Abe visited Trump Tower on November 17th before attending the APEC Economic Leaders’ Meeting in Peru.

The parallel is particularly noteworthy given the former rivalry between Ishiba and Abe within Japan’s political landscape.

Abe’s memoir reveals his strategic reasoning for the early Trump Tower visit.

He recognized the urgency of establishing trust, particularly given Trump’s campaign rhetoric questioning the Japan-US alliance, including his opposition to the Trans-Pacific Partnership, accusations of Japan “cheating” in exchange rates, and criticism of Toyota.

However, Yoichi Funabashi’s October 2024 biography of Abe, based on extensive interviews with key figures, reveals the carefully orchestrated nature of this engagement.

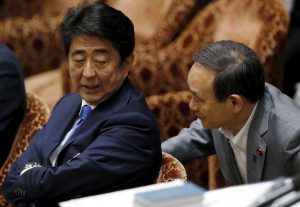

The groundwork began during the September 2016 UN General Assembly, where Abe met with Wilbur Ross, who later became Commerce Secretary, as Trump’s representative.

Three days before the election, Abe’s team initiated contact with Trump’s campaign regarding a congratulatory call.

Then Chief Cabinet Secretary Suga, the architect of this approach, dismissed concerns from Foreign Ministry officials with characteristic pragmatism, stating, “If Trump loses, we can simply ignore it.”

Abe’s memoir outlines three primary objectives for the Trump Tower meeting: strengthening security cooperation in light of China’s military expansion, highlighting Japanese economic contributions to the US, and establishing a personal connection through golf diplomacy.

While Abe ultimately played golf with Trump five times across both countries, Ishiba’s focus will likely center on security and economic matters.

The security dialogue has already begun promisingly, with Ishiba emphasizing the Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) concept.

The FOIP concept first came up during Abe’s first reign as Prime Minister in his 2007 “Confluence of the Two Seas” speech to the Indian parliament, but he subsequently elaborated upon that initial vision in an August 2016 address in Nairobi by declaring that “Japan bears the responsibility of fostering the confluence of the Pacific and Indian Oceans and of Asia and Africa into a place that values freedom, the rule of law, and the market economy, free from force or coercion, and making it prosperous“.

Trump was quick to take the FOIP idea on board, telling the November 2017 APEC CEO Summit in Vietnam that “I’ve had the honor of sharing our vision for a free and open Indo-Pacific — a place where sovereign and independent nations, with diverse cultures and many different dreams, can all prosper side-by-side, and thrive in freedom and in peace“.

Abe, too, proclaimed in his January 2018 policy speech to the Diet that “we will promote the Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy“.

The United States Pacific Command (USPACOM) was subsequently renamed the United States Indo-Pacific Command in May 2018.

Funabashi’s biography notes that Japanese officials later emphasized to Kurt M. Campbell, then part of Biden’s transition team, that FOIP originated with Abe rather than Trump. Ishiba’s adoption of this framework, rather than his previous advocacy for an “Asian NATO,” signals strategic continuity in Japan’s foreign policy approach.

Trade and exchange rates are liable to be the main sticking points.

In a July 16 Bloomberg interview Trump started out by referencing Abe’s untimely demise at the hand of an assassin: “I thought he was so great. What happened to him was so sad. He was a very good friend of mine“. But he then went on to criticize what he saw as an imbalance in US-Japan trade: “How many cars you see going into Japan? I said, ‘Shinzo, I don’t see any Chevrolets down here. I’m not seeing the Chevrolets. Where are the Chevrolets?’ But I see lots of Toyotas and every other make of car“.

And he furthermore spoke of “a big currency problem” and alluded to a need for tariffs: “I’ve been talking to manufacturers, they say (…) nobody wants to buy our product because it’s too expensive. You look at Komatsu and these tractor companies. They make a good product but you know—[lack of price competitiveness is] going to force Caterpillar and these other [US] companies (…) to build in other nations“.

Funabashi claims that Trump had from the time of the 2016 election complained about the greenback’s strength eroding the international competitiveness of US manufacturers and exacerbating the US trade deficit, and that the greatest fear of Abe and his Finance Minister Taro Aso was that the Trump administration would pursue a “weak dollar” policy and thereby trigger a renewed and unwelcome rebound in the yen.

Bloomberg’s aforementioned July interview does indeed suggest that Trump has in no way changed his stripes.

Abe ended up meeting with Trump on 14 separate occasions after the latter’s inauguration and having a total of 35 telephone conversations.

Part of the reason (as per Funabashi) for this frequency was that Trump was unable to shake off his engrained impression of 1980s-era Japan, meaning that it was basically necessary to start from scratch on each occasion and then effectively bring Trump “back up to speed” on current reality.

Funabashi’s biography also offers what is tantamount to advice from Abe on how to get along well with Trump.

First, “Abe knew that Trump isn’t all that interested in policy and doesn’t read policy papers or even look at the prepared talking points, and thus from the beginning opted to skip the details in favor of more general storytelling”.

Second, Trump more than anything despised “losers”, and saw everything in terms of “winning” (and how often) or “losing”. He was thus impressed by Abe’s victories in the 2017 lower house and 2019 upper house elections and would discuss election strategy in some detail with his fellow “winner” almost every time they spoke.

Third, Abe said that it is pointless to attempt to persuade Trump into a straight “yes” answer.

Ishiba’s ability (or otherwise) to learn from Abe and build a sound working relationship with Trump could ultimately end up having very significant ramifications for not only his own administration’s longevity but also the Japanese economy and financial markets.